Self-calibration

If you’d be a robot but the mechanic that always calibrates you and keeps you well-oiled was on vacation, how would you make sure that you would keep functioning? Your sensors might run amok, and you might fall over as a result. It just so happens that we are biological robots without mechanics. How do our brains keep our senses and actions calibrated so that our goal-directed behaviour is exactly that, goal-directed?

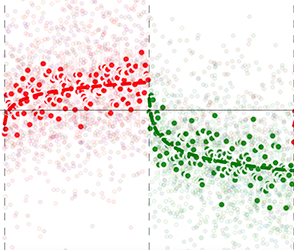

It calibrates itself. One nice example of this is saccadic adaptation, the process by which the brain keeps your eye movements landing on target. After every eye movement, the landing position of the eye is compared to the visual input, and any error the brain finds is then corrected through an adaptation process. We can hijack this adaptation process if we use a fast eye tracker and screen. During the 30 or so milliseconds that your eye is in flight and you’re rather blind, we can change the position of the target of your eye movement. Your brain registers this as a mismatch between the intended and actual landing position, and adapts: the next eye movement will make less of this error. If we keep doing this over and over, your eye movements can be shrunk or grown by as much as 30-35%, even without you being aware of it (see the figure, for example).

It calibrates itself. One nice example of this is saccadic adaptation, the process by which the brain keeps your eye movements landing on target. After every eye movement, the landing position of the eye is compared to the visual input, and any error the brain finds is then corrected through an adaptation process. We can hijack this adaptation process if we use a fast eye tracker and screen. During the 30 or so milliseconds that your eye is in flight and you’re rather blind, we can change the position of the target of your eye movement. Your brain registers this as a mismatch between the intended and actual landing position, and adapts: the next eye movement will make less of this error. If we keep doing this over and over, your eye movements can be shrunk or grown by as much as 30-35%, even without you being aware of it (see the figure, for example).

We use this phenomenon to study eye movement planning and attention - processes important for all visual experience, but also for things like reading, and driving a car.